“My work started from language,” visiting artist Andrea Carlson says of her career as a storytelling and an artist. Storytelling in Carlson’s Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) culture is a living tradition, where the philosophy of language differentiates between the animate and inanimate.

On Wednesday, November 1, 2017, Andrea Carlson’s Ravenous Eye Exhibition opened in the Art Gallery. Before the Opening Reception of her exhibition, Carlson discussed the trajectory of her work. Her first series of paintings focused on the act of storytelling, although Carlson had to reconcile for herself the fluidity of life in the Anishinaabe tradition with the fixed state of a painting.

“We put identity onto objects that are nestled into culture,” Carlson says, speaking on her first series of paintings that recontextualized the object-nature of paintings. She painted various objects on display at Minnesota museums, reframing those objects from their glass-case surroundings to positioned against foreign landscapes.

These landscapes were heavily inspired by the backdrop of Northern Minnesota and Lake Superior, where Carlson grew up. The water line of Lake Superior is a recurrent image in Carlson’s work, invoking the infinite. Landscapes are paths through the artwork, telling their own story through navigation.

Carlson’s work is notable for its scale. Ink Babel is a 10- by 15-foot mural that comprises 60 pieces of paper arranged in a grid, with most duplicated images hand-drawn to be organic. Carlson works almost exclusively on paper because it allows a fluidity of materials, as she variously employs acrylic and oil paint, watercolor, gouache, pen and ink, and graphite and colored pencil.

Museums – or “white walled boxed spaces” that “hoard and consume” other worlds, as Carlson described them – are perpetrators of colonization. Museums have the authority to decide cultural importance, based on the objects they display, the arrangement of the display, and the textual blurb that tells the viewer a compact history of said object. Carlson rewrites cultural narratives and challenges assumed institutional authority.

Concerned with the process of assimilation and cultural appropriation, Carlson applies cannibalism as a metaphor for the consumption of cultural identity. Her “Windigo” series, named for an Anishinaabe winter cannibal whose hunger only grows the more he eats, mimics the greed of assimilation. The windigo’s misidentification for those he consumes resembles the colonizer’s dehumanization and othering in order to justify subjugation. Quite literally, as Carlson says, “colonization is the consumer of the other.”

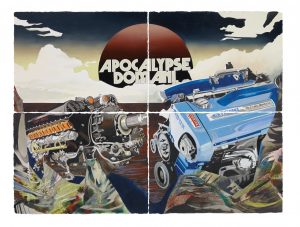

Carlson’s later work has shifted to the role of objects as symbols of power, as depicted in Apocalypse Domani. The increasing scale of her work shifts the power balance between viewer and artwork. When the artwork is larger than you as the viewer, you are “visually getting chewed on,” Carlson relates.

Carlson thrives in the contemporary, criticizing the sense of authenticity. Her work, her life, her heritage all exists in the now. Carlson says she seeks to “antagonize time constraints” in her paintings, blending traditional motifs with modern art. Moving forward, Carlson admits that she is “intentionally getting more abstract” in her work, allowing her iconography to confuse the viewer in order to make them rethink their position. In allowing the viewer their own freedom of interpretation by not providing a codex to explain each metaphor, Carlson learns about the effect of her work on others.

The concept of authenticity is a weapon used by the colonizer to deny a life in the present moment. Carlson reimagines a space in the future for Native American peoples to assert themselves so that they cannot be erased.

Carlson says that each piece has humbled her as she has worked on and presented it. Storytelling modes have shifted and the conversation on colonization is becoming more global. Modernity has allowed Carlson to imbed aspects of film into her work, as she views film as a global, shared system of storytelling that can connect us. Upcoming next year, Carlson will debut Ink Babel’s sister piece, which will be in full color, as opposed to Ink Babel’s monochronism.

When I first started thinking about making Ink Babel, I wanted to produce a work that was organized around the horizon line but a horizon that couldn’t be seen all at once. The Horizon is the traveler’s storied crust. It is always just out of reach and is symbolically filled with potential stories, quests and sagas.

– Andrea Carlson

Text by Shannon Kelly